By Christopher J. Owen

It was a bright Tuesday morning when I sat down with internationally renowned drag queen Cheddar Gorgeous. Known for her unicorn, alien, and other fantastical drag performances, Cheddar Gorgeous is one of the UK’s most celebrated drag queens with over 94,000 online followers. The ‘drag daddy’ of the Family Gorgeous, Cheddar is one of the driving forces of Manchester’s Home of Fabulous, Cha Cha Boudoir, an infamous and inclusive late-night club cabaret for spectacular creatures. More recently, Cheddar is one of the stars of Channel 4’s new hit show Drag SOS.

Out of drag, Cheddar is known as Michael Atkins. Dr. Atkins has a PhD in Anthropology from the University of Manchester. His research explores sex work, public sex, fluid identities, and gay villages.

We sat down to talk at Katsouris, a Greek deli on Deansgate in Manchester. Cheddar tucked into a vegetarian breakfast as we began to chat about her drag and its relationship to science fiction and fantasy.

Christopher Owen: What is drag to you? What is your drag and how do you approach drag?

Cheddar Gorgeous: I think trying to define drag is quite a difficult task. And obviously a lot of the time I think it’s been reduced to a form of theatrical cross-dressing, and that for me is never really what interested me in drag. A lot of what I’ve been thinking about for the past few years is: if we don’t take that definition of drag to be about theatrical cross-dressing, what is it that all the different kinds of drag that we see happening and share, what is it that we do collectively? Because when you look at all the different kinds of performers that defines a drag queen, many of them don’t give that theatrical cross-dressing model. Sometimes they are women embodying some kind of femininity, sometimes they are men who are playing with both masculine and feminine things, sometimes they are involved in the kinds of transformations that don’t seem to be about gender at all, and certainly aren’t about a straight board of gender binary transformation. So, if we’re to think about drag, what is it that we all share and how would you then define drag? For me, it’s about trying to become a spectacle that lives, and is part of people’s relationships, and has a life beyond any particularly defined moment. I think it’s very much about channelling something within ourselves. For me, I really think it is about taking that thing that you think people don’t see about you in your everyday life and making it the only thing they can see.

And so for me drag has never been about being able to channel a particular feminine energy, or at least the energies I wanted to channel I didn’t associate with becoming like a woman or performing like a woman. My drag has never really been too feminine. I started out by doing campy female sort of drag, but very quickly moved on to stuff that was a lot more gender-fluid, a lot more androgynous, and sometimes even actually turning masculine stereotypes into something fabulous. And then, as I’ve grown, I’ve gravitated much more to the things that are a little bit less human. I look for stuff that transcends the human a little bit, or transforms the human a little bit, and plays a bit more with being monsters, gods, aliens, dragons, all of those kind of big fantasy and science fiction archetypes.

CO: Why?

CG: Because when I was a kid, they were the things that inspired me, but also they were the characters that I recognised as powerful. And I think if we go through that idea of drag as a way of connecting with the things people don’t see about us, drag was my way of becoming powerful and having a voice and being seen.

I was a very shy, unassuming teen, who didn’t go out a lot and couldn’t get a girlfriend or a boyfriend. And for me, drag was a way of making myself larger than life. And I associated the larger than life not with the female icon up on the stage, but for me it was aliens from Star Trek, it was the big bad guys in fantasy films, it was demon from Legend. So all the characters that I saw as having something special, and having something powerful about them, and literally having power, they had these ways of affecting change in the world and ways of making things happen that was like beyond the human, and I think that’s very much something that I wanted to connect with in my drag. I wanted to find my own voice about causes and things I care about, and my own welfare like making money and living my life.

CO: How were you first introduced to science fiction and fantasy, and what is your relationship to these genres?

CG: When I was a kid there was a slot on Channel 2 that always had something that was fantastical, like Star Trek, and as more shows came out I got into more of them. I think I loved the extraordinary, I loved the escape from normality. But also, looking back, I don’t know how much I am projecting into the past a recognition of difference. I don’t know whether as a child I saw in those characters some kind of queerness and a difference about them that I then gravitated towards, or if being exposed to so much of that made me have an appreciation for queerness and difference and a longing to stand out and be those characters. I don’t know which way around that worked, but I definitely think for me there’s a relationship between science fiction, fantasy, the fantastical, queerness, and my own queerness. And I don’t know which one pushed which, but the two have certainly grown together, and the ways that I longed to make myself visible are so bound up with all of those archetypes. Those years of watching have affected everything that I do, and the way that I see romance, the way that I see tragedy, the way that I see heroism, and as the genres grew up and changed, so have my ideas about those things. But it’s interesting how so many of my years as a teenager and young adult were influenced by the stories that were taking place in these fantastical worlds.

I was a bullied kid, and it seemed natural to gravitate toward science fiction because that’s what bullied kids watched. But it opened up a world that feels like a really privileged world, it opened up an exciting world, it opened up a realm of possibility that I think people who aren’t bullied don’t get access to. And it’s weird: was I bullied because I was a geek, or was I a geek because I was bullied? I don’t know. And so I don’t think it’s necessarily always about being gay, I was just rejected as a kid: I had glasses, I had ginger hair, I had bad skin. I felt like an outcast, and so maybe I sourced my outcast-ness from these strange and wonderful creatures. Science fiction is much more readily able to explore those kinds of characters, because you can literalise them. You can make them literal, otherworldly beings, you can make them aliens. And that I think is how a bullied child feels sometimes. They’re so radically different from the people they perceive around them that they’re an alien, or that they are a monster. So I think that there’s definitely a resonance with that which is why I got into science fiction. Feeling like an outcast.

CO: Your unicorn look, I feel, is one of your more iconic looks. Talk to me about where that comes from.

CO: Your unicorn look, I feel, is one of your more iconic looks. Talk to me about where that comes from.

CG: It’s a fantasy, it’s a full on fantasy.

CO: Absolutely, and it’s a unicorn person. It’s an anthropomorphised fantasy. Where does that come from? What is its history?

CG: Unicorns are just a bit of a cultural sensation, aren’t they? And they have been for a number of years now. It happened accidentally. I was given a unicorn horn by some guys who I knew from the club, who had done it once for fancy dress, and were never going to wear a unicorn horn again. So they gave me their unicorn horn. So I thought, ‘well I’ll do that sometime,’ and I put it in a drawer. And then one day I did it for a party. But I wanted to do it in my own way. Usually when someone does a unicorn look they do it with hair and it’ll be like a full horse fantasy. But I just wanted to do a bald look. I enjoy being a unicorn, and it became a surprisingly powerful identity for me and has become that. Prior to that it was very much a faun, I was really into fauns before I got into unicorns. And a faun is very much a male energy.

CO: I was going to ask you about your faun look next!

CG: The faun has a very male energy and has a history of being very male and with various different nature spirits and the great god Pan and connecting to that kind of storytelling around a kind of almost animalism, a sort of connection to animal sexuality. All those gods, that’s what they represented: debauchery. Fauns are known for aggressive sexuality.

But the unicorn has this other resonance which is both male and female. Unicorns are camp, they’re sparkly, they are cute creatures, yet they have a fucking horn on their head, they can defend themselves, and they drink blood. In a mythological way, they have this kind of surface level beauty and cutesiness, and they’re seen as fun and approachable and for everyone, and yet they have this darker other narrative history. And I just think it’s such a wonderful combination to go together because they’re complicated beings. So I think I’ve always gravitated toward that. I just love that. It’s such a nice mix to be able to put out a look that is both sparkly and beautiful yet also a bit scary and aggressive.

But the unicorn has this other resonance which is both male and female. Unicorns are camp, they’re sparkly, they are cute creatures, yet they have a fucking horn on their head, they can defend themselves, and they drink blood. In a mythological way, they have this kind of surface level beauty and cutesiness, and they’re seen as fun and approachable and for everyone, and yet they have this darker other narrative history. And I just think it’s such a wonderful combination to go together because they’re complicated beings. So I think I’ve always gravitated toward that. I just love that. It’s such a nice mix to be able to put out a look that is both sparkly and beautiful yet also a bit scary and aggressive.

But yeah, I was a faun before. I did a lot of stuff with horns, and nature, and bark, and I think that was about allowing me to connect with that aspect of myself. With stuff around sex. With stuff around what I needed and want and that kind of thing.

CO: You said that fauns are associated with aggressive sexuality, can you expand on that?

CG: With aggressive sex and debauchery, yes. With a kind of need, and a lack of control. I think I’ve always been a very controlled person, so playing with those characters allowed me to safely connect with that kind of energy. And obviously not some of the terrible associations. They were a bit rapey. So not that energy. But still, a letting go.

The earlier stuff I did was a lot about the awakening of nature. And it was about darkness. I did a performance that was about the tension between technology and nature, between darkness and light. And the great god Pan represented uncertainty, as well as all those desires, and the storm of desire, it also represented the darkness of the woodland. The myth of the goat god comes from the noises you would hear at night and couldn’t identify, so it’s bound up with the idea of ambiguity, and ambiguity is something that causes us a great deal of discomfort. And it’s where we often like to place desires psychologically, as it were. But maybe my attitudes now are a little more serene when it comes to that kind of energy. I’ve moved on.

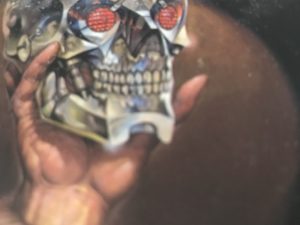

CO: You were talking about technology and the darkness of technology, and you’ve got several robot looks as well.

CG: I do a lot of robot stuff, yeah.

CO: Talk to me more about this. You’ve moved from nature and myth to machine and alien.

CG: I’m really into Westworld and Blade Runner and all of that kind of stuff, and imagining what the eventual future of humanity is. And I truly believe that the future of humanity is artificial intelligence and that we will die but that, you know, the logical next stage of our evolution is not us at all but is the stuff that we will create and will outlive us. The point of tension that is interesting for humans is where those two worlds overlap. Robots won’t be interested in it. We wouldn’t be interested in what life will look like, because I don’t think it will resemble something we will relate to, but that bit in between, where robots resemble people, and people start to be more like robots, that’s interesting. And the robot’s a great metaphor for allowing us to think about what it means to be human. Not only in questioning where is the boundary between a human and a machine, but also how humans can be so much like machines.

CG: I’m really into Westworld and Blade Runner and all of that kind of stuff, and imagining what the eventual future of humanity is. And I truly believe that the future of humanity is artificial intelligence and that we will die but that, you know, the logical next stage of our evolution is not us at all but is the stuff that we will create and will outlive us. The point of tension that is interesting for humans is where those two worlds overlap. Robots won’t be interested in it. We wouldn’t be interested in what life will look like, because I don’t think it will resemble something we will relate to, but that bit in between, where robots resemble people, and people start to be more like robots, that’s interesting. And the robot’s a great metaphor for allowing us to think about what it means to be human. Not only in questioning where is the boundary between a human and a machine, but also how humans can be so much like machines.

Ways of communicating are now often through a digital world. As we become more bound up with certain kinds of digital technologies, the ways that we think, the ways that we move, and the ways that we interact with one another, take on an almost metaphorical value that’s almost like programming. It almost becomes predictable. The kind of unruliness of human behaviour is becoming more and more systematised, and I think that’s a really interesting way to think about how our economies work, how people’s interactions work. And sometimes there’s a little bit of a warning. But perhaps that’s me being too bleak about technology. But I think like anything, I’m really excited about the idea of an interconnected humanity. A genuinely empathic, interconnected humanity facilitated by digital technology. I think the real danger with technology comes not through technology itself, it comes through the way it is exploited by the systems of our economies, the systems of certain things in our cultures. The idea of individualism, the idea of capitalism, that’s where the danger occurs. So I’m not at all anti-technology, but I’m aware of its power to shape humanity and its ability to be used to shape our future.

CO: And so with your technological drag, is the thing you want them to see that tension?

CG: Yeah, and to trouble it. To trouble what it is to be human. To play with it. When I do performances, I’ll do things like sex-slave robots, and I also have a Westworld performance. When I get into putting on that drag and being that kind of drag, I’m less interested in the wider big questions about humanity. I wonder what it would feel like to be a self-aware robot. That’s interesting. And to use it with tragedy. Quite like Ex Machina. What is it to be a new kind of life? It’s exciting but also scary. At what point do we only recognise that which is only pretending to be human, emulating or copying humanity, and to what purpose would that serve for a machine? Will our technology inherit the shit of their parents, in the way that we did, or would it only be there for strategy and aesthetics? I think all of that stuff’s really interesting.

CO: I want to ask you about your alien look.

CO: I want to ask you about your alien look.

CG: All my stuff’s a little bit alien-y. It’s like an entire theme. I do a lot of star-man like stuff. Like a visitor to the planet. The idea of a being that is not from here is a great narrative device. What you’re doing is telling a story, you’re communicating with people. And that idea of a person who sees the world from the outside is a great position to pretend to come from, because I’m not from the outside. But as a kind of way at looking at humanity, and being able to say something about humanity, it’s a nice position to imagine. And I think that would be one of the things I would be clear about: I don’t believe in objectivity, it’s an imagined objectivity, but it’s quite a nice game to play with the drag. So the alien aesthetic runs throughout all of my work. Or, maybe it would be more fair to say, the idea of being outside of what is human runs throughout all my work. I never do a traditional beauty, I never do something that looks like a human. As my drag’s progressed, I’ve removed the things that make me look human, like my eyebrows. I never ever do eyebrows in drag anymore. I do occasionally do hair, but more and more it’s about being less like a human person.

CO: You also have looks like Doctor Manhattan, that show that you’re a science fiction fan. So let’s talk about you as a fan, and fan culture. Let’s talk about your fan response, and your relationship as a fan to science fiction.

CO: You also have looks like Doctor Manhattan, that show that you’re a science fiction fan. So let’s talk about you as a fan, and fan culture. Let’s talk about your fan response, and your relationship as a fan to science fiction.

CG: Aren’t characters in science fiction and fantasy way more interesting than any real world celebrity? Like, why on earth would I care about Ariana Grande or Miley Cyrus when I’ve got gods and aliens and beings created in nuclear experiments to wake up to? I’ve never been good at being a fan. When David Bowie died, I realised I was his fan. I realised that’s a person I look up to and love and adore.

CO: And you have a David Bowie look as well.

CG: Yes, and it makes sense. Right? Because his entire shtick transcended humanity. He turned his death into an art piece. How very not human of him. He defied culture. And I think there’s something about positioning yourself as an outsider. I do a lot of Bowie stuff; it’s about this idea of how a person can come into the world, tell a story, play a part, shape ideas, and leave. Which is a metaphor for life. It’s a powerful metaphor for life. And what every human has the potential to do for each other.

We have the potential to come, change minds, think about things, grant new perspectives. In drag you get to do that: you get to be so radically different and be a spectacle. But maybe just by being in the room you can challenge people’s ideas about who they are, who they can be, and the potential of who they might be, which is what science fiction and fantasy does. That’s one of the joys of science fiction and fantasy: there are no rules. It allows us to create these potential futures, potential pasts, potential presents, and that has a power to actually make shit happen. You know that there is shit that exists today because it happened in Star Trek, and that’s amazing. Think of what kinds of worlds we might be able to shape, the wonderful and terrifying possibilities. I think drag is just a way that I try and make that a little more real and put it into the world.

We have the potential to come, change minds, think about things, grant new perspectives. In drag you get to do that: you get to be so radically different and be a spectacle. But maybe just by being in the room you can challenge people’s ideas about who they are, who they can be, and the potential of who they might be, which is what science fiction and fantasy does. That’s one of the joys of science fiction and fantasy: there are no rules. It allows us to create these potential futures, potential pasts, potential presents, and that has a power to actually make shit happen. You know that there is shit that exists today because it happened in Star Trek, and that’s amazing. Think of what kinds of worlds we might be able to shape, the wonderful and terrifying possibilities. I think drag is just a way that I try and make that a little more real and put it into the world.

CO: And on that note, what is the future of science fiction and fantasy’s relationship with drag?

CG: Kids are doing it. Especially with cosplay. They’re playing a role, yes, but they’re allowing themselves to embody these ideas. Kids are allowing themselves to be their heroes. And that’s exciting. The cosplay community is amazing.

CO: Would you say that cosplay is separate from drag?

CG: I think it’s separate because with drag you make it your own; it’s no longer about being someone else. Drag may draw inspiration from different things and people, but it is not becoming a replication of what you see someone else being. I think cosplay is amazing. It’s a different thing to me, and there’s no hierarchy; they’re related but different.

CO: But you do see the relationship between science fiction and drag growing more in the future?

CG: I think as our social world, and how we view gender and our identities and our class and all that stuff, and as we become more aware and these things become more complicated, I think you’ll see more people turn to science fiction both in the way they do drag, but also in the way they project their identities in their everyday lives. All of our identity politics sort of borrow from sci-fi; I think people don’t give it the credit it deserves for how it shapes, and how it has shaped our ability to change culture. Science fiction allows us to view things like race and gender in new and exciting ways; characters can be neither male or female, and viewers can think “I’m going to be like them.”

I think drag is ultimately a reflection of what’s going on in our world, so I think the relationship between more broad identity politics, politics, culture, society, science fiction and drag, they all emerge from one another and evolve from one another. It’s all a big soup, really.

CO: So what’s next for Cheddar Gorgeous?

CG: I’ve just done a TV show, Drag SOS. It’s all about allowing people to connect with their own fantastic selves. The TV show is about working with people to help them find that little bit of magic and fabulousness inside themselves. And it is magic. Because that’s where the energy comes from for me.

It’s the first ever mainstream UK TV show to focus on drag as a subject matter. It’s certainly not the first UK show to feature a drag queen–drag queens have been on TV for years, take Lily Savage for example–but this is the first show about drag. And what I love about the show is that at its centre is the idea that drag’s power is in community, rather than power in competition. So we have community at the heart of our show, rather than competition. And I think that’s something very distinct about British drag. Here drag is very much about bringing people together to tell stories, further causes, and to have a good time. It’s not about who is the best. Very little about British drag history has been about being perfect, and I think that’s quite a special thing we need to hold on to.

CO: Any final thoughts?

CG: Keep being a weirdo.

You can see more of Cheddar Gorgeous on Channel 4’s Drag SOS, airing Tuesdays at 10.00 pm. Follow Cheddar online at instagram.com/cheddar_gorgeous

[*responses were edited for clarity and brevity]