By Nina Allan

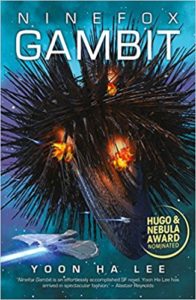

Ninefox Gambit — Yoon Ha Lee (Solaris)

The SF Encyclopaedia informs us that the term ‘space opera’ was first introduced into science fiction terminology by writer and editor Wilson Tucker in 1941, who coined it as a spin on the already familiar terms ‘soap opera’ and ‘horse opera’ to describe any ‘hacky, grinding, stinking, outworn, spaceship yarn’. Wikipedia goes on to define space opera in the modern era as being ‘a subgenre of science fiction that emphasizes space warfare, melodramatic adventure, interplanetary battles, as well as chivalric romance, and often risk-taking. Set mainly or entirely in outer space, it usually involves conflict between opponents possessing advanced abilities, futuristic weapons, and other sophisticated technology’.

The SF Encyclopaedia informs us that the term ‘space opera’ was first introduced into science fiction terminology by writer and editor Wilson Tucker in 1941, who coined it as a spin on the already familiar terms ‘soap opera’ and ‘horse opera’ to describe any ‘hacky, grinding, stinking, outworn, spaceship yarn’. Wikipedia goes on to define space opera in the modern era as being ‘a subgenre of science fiction that emphasizes space warfare, melodramatic adventure, interplanetary battles, as well as chivalric romance, and often risk-taking. Set mainly or entirely in outer space, it usually involves conflict between opponents possessing advanced abilities, futuristic weapons, and other sophisticated technology’.

Incredibly, the magazine stories that first came to define space opera were written almost a hundred years ago. The common wisdom within SF circles is that space opera has come a long way from its pulp origins, and that the term – very much a pejorative when it first began to be used – now encompasses a wide range of very different works, with differing levels of ambition. While there still seems to be a strong popular appetite for the kind of space opera that stresses the battles-and-adventure component of the equation, we see an increasing number of authors who are using the conventions and templates of space opera to present stories that, through their structure, character demographic and emphasis on social and political concerns are extending the risk-taking portion of the equation beyond the frame of the narrative and into the rationale for the story itself.

That’s the theory, anyway, though examples of truly innovative space opera remain few and far between. While an increasing number of writers have made strenuous and laudable efforts to confront the ‘boys’ own adventure’ stereotypes of core genre archetypes – the most famous recent example being Ann Leckie’s Imperial Radch trilogy – progressive experimentation and stylistic complexity in terms of the text itself is much, much rarer and receives scant notice. When Yoon Ha Lee’s Ninefox Gambit turned up on this year’s Clarke Award shortlist, of the three books I’d not read already it was definitely the one I was most excited about. My encounters with Lee’s short fiction had left me with an impression of complex ideas nestled within a prose that was dense and highly coloured and often abstruse – pluses for me on all three counts. Would Ninefox Gambit prove to be my space opera holy grail: a thrilling adventure in terms of prose as well as high-concept, widescreen FX? I was eager to find out.

Returning to the Wiki definition of space opera – space warfare, melodramatic adventure, interplanetary battles, conflict between opponents possessing advanced abilities, futuristic weapons, and other sophisticated technology – Ninefox Gambit places a tick in every box. Lee imagines for us a strictly stratified society in which opposition or ‘heresy’ among individuals is almost literally unthinkable, and at the planetary level punishable (shades of the Imperial Radch here) by assimilation, obliteration, or a sequential combination of the two.

Our hero is Cheris, a captain in the Kel, the hexarchate’s military caste whose training is based around the doctrine and programmed defensive manoeuvre of formation instinct. Cheris is tasked with putting down a nascent insurrection, a rebellion that threatens to destabilise the calendar on which the security and viability of the empire depends. Along for the ride we have Jedao, a general of the Shuos, a class that consists mainly of assassins and master strategists. The problem for Cheris is that Jedao is dead – executed four centuries before for treason and mass murder – and that access to his remarkable military prowess is available only through a risky fusion at the mind-body level.

As Cheris gets to know Jedao better, we see her sympathies begin to shift. But is her too-close cooperation with the renegade general compromising her judgement, and who exactly is using whom when it comes to strategy? As a deadly endgame approaches, we learn the answers to some of these questions, which in turn present us with a whole new series of questions that will presumably be addressed in this first book’s upcoming sequel.

After a somewhat confusing opening segment – the kind that has you flicking backwards through the pages as you try and get to grips with exactly who everyone is and who is fighting whom – the narrative settles down into a relatively straightforward military adventure story. Cheris’s taskforce sets course for the Fortress of Scattered Needles, where the calendrical insurrection is taking place. There’s a horrific battle that culminates in the scouring of an entire ward of the fortress with quantum weaponry and a resultant 46,000 collateral civilian casualties. As the ashes smoke the cavalry arrive, only they turn out not to be the cavalry at all, or at least not for Cheris. As General Shuos Jedao is torn apart by exotic technology, Cheris has a critical decision to make. And who, exactly, is piloting the needlemoth that exits the scene? Again we can make our guesses, but we’ll have to wait for the next instalment of the trilogy to find out for sure.

Once you’ve pinned down the parameters of Lee’s world, it is not too difficult to write a summary of what his novel is ‘about’. When it comes to assessing Ninefox Gambit’s literary value though, I feel genuinely torn. It’s a neat text, a clean text, a carefully balanced equation with every value checked and in place. It is clear from the tidy way the story works itself out that Lee has command of his material and delights in using it. Lee clearly has well defined ambitions for his project: to present a space opera that delivers on excitement and grandiosity whilst balancing those excesses with a thought-provoking magic system (because really, that’s what the calendrical system is in everything but name) and a timely meditation on the nature of war, loyalty, betrayal and empire. The prose does not have the density of a lot of Lee’s shorter work but there are flashes of that brilliance here and there, as well as an intuitive personal awareness of literary values:

Her breath hitched as she examined a twisted arch of carrion glass. It had once been Commander Hazan. There were faint threaded traces of a tree he had loved as a child, a sister who had died in an accident, things she had never known about him.

There is, too, an evident desire to highlight the cost of war in human terms, to evaluate its damage:

She read about a child. A woman. A man trying to carry a crippled child to safety. Both died bleeding from every pore in their skin. A woman. A woman and her two-year-old child. Three soldiers. Three more. Seven. Now four. You could find the dead in any combination of numbers.

Faces pitted with bullet holes. Stagnant prayers scratched into dust. Eye sockets stopped up with ash. Mouths ringed with dried bile, tongues bitten through and abandoned like shucked oysters. Fingers worn down to nubs of bone by corrosive light. The beaks of scavenger birds trapped in twisted rib cages. Desiccated blood limning interference patterns. Intestines in three separate stages of decay, and even the worms had boiled into pale meat.

There are further graphic descriptions of the effect of exotic weaponry on human bodies, and yet for me at least there is not enough to counterbalance the general distancing wrought by the widescreen, space-operatic approach of this kind of fiction. The key decisions occur in the control room, between persons of power. There is some talk along the lines of ‘war makes monsters of us all’, but given that the vast bulk of what passes for action in Ninefox Gambit results in the impersonal destruction of literally millions of people, I’d say not enough.

Even setting aside any moral objections, my main beef with this novel is that for a work of so-called military SF, it gives the reader next to zero insight as to what war actually entails. Civilians are simply ‘squirrels’, barely glimpsed running in a futile, disorganised and vaguely pitiable manner away from the theatre of battle. What’s it like to be a simple soldier in the armies of the hexarchate? Once again, we have no idea. (It’s interesting to note that one of my personal shortlist choices, Steph Swainston’s Fair Rebel, falls prey to a similar weakness. We get to see the generals, the immortals, their expressions haggard with guilt at the fate of their favourites, but the thousands of soldiers that serve under them are basically Insect-fodder.)

This is not so much a moral failing as poor imagining, a point reiterated still more strongly when considered against the general ambience of the novel as a whole. Although Lee’s prose is distinctive for its clear refinement and poetic sheen, the narrative itself has about as much visual and emotional texture as a series of crossword clues slotting neatly into place. I could probably tell you something about the uniforms these people wear, and their (ahem) House Sigils, but for all the information we are given about buildings, rooms, planets, spacecraft, cities, landscape, the action may as well be taking place inside a games console. After reading more than three hundred pages I am still unable to decide if the Fortress of Scattered Needles is a vast space station, an artificial satellite or a fortified garrison on an outlying planet. There are pet deer there, that’s all I know. Or at least there were before the threshold winnowers were switched on. (I refuse to say ‘activated’.)

The dialogue, all too often, reads like something out of Star Trek: characters explaining the plot to each other in solemn voices or asking pointed questions to underline the moral point or narrative twist that is about to be made.

“A million people dead four centuries before you were born, and you care about them. It speaks well of you, even if it doesn’t speak well of me.”

There are ideas in this novel that appeal to me and that I wanted to know more about – the squaring-off between Nirai Kujen and Shuos Jedao, for example, in which it is revealed that Jedao’s ambitions have been thwarted by his poor grasp of higher mathematics:

“I don’t know how it escaped everyone’s notice for so long that you have dyscalculia. Math was the only subject you struggled with, isn’t that right? You need number theory to get anywhere in high level calendrical warfare. Nine hundred years ago I invented an allied branch of math to make the mothdrives possible. No one else has successfully pulled off a major calendar shift. I’m surrounded by tinkerers, not real mathematicians.”

I longed for a deeper, more psychologically complex exposition of these theories, a broader consideration of what a philosophy of government founded upon the principles of mathematics might actually be like, how it might alter our own perception of reality. Yet I could never escape the sense that what I was actually being given was the literary equivalent of two guys in robes duking it out on the bridge of the Enterprise, fighting over who got to press the self-destruct button.

Only in the final fifth of the novel, when Cheris swallows carrion glass and internalises the general, do we finally gain some insight into character and psychological motivation: here we are offered glimpses of Jedao’s past as a young officer, as a student, as a man who made a terrible mistake. The writing is richer here too, more certain of itself, more driven and more fully integrated with the novel’s thematic purpose. All the more pity then that many readers – and most especially those not fully acquainted with the assumptions, frameworks and operating systems of space opera and MilSF – could find themselves giving up on the novel long before they reach its catharsis.

Does Ninefox Gambit deserve its place on the Clarke Award shortlist? Again, I find myself torn. The book is skilfully made, cleverly thought through, and clearly the product of a vibrant imagination. I deeply appreciate the attitudes to gender and sexuality that characterise this text. Ninefox Gambit showcases an unforced, free-flowing diversity that forms one of the natural building blocks of the narrative and worldview rather than existing self-consciously as its central focus, and enters as a breath of fresh air (more like this, please) into a subgenre where gender roles have traditionally either been woodenly, offensively conservative or so deliberately subverted as to render the effect a cliché in its own right.

In the end though, what do we have? I would never go so far as to label Ninefox Gambit as any old ‘hacky, grinding, stinking, outworn, spaceship yarn’ – it’s too self-aware and too well executed – but the fact remains that as science fiction, it is very traditional: evil empire, Death Star, Federation versus heretics, the lot. Several themes within the novel show potential for serious contemplation within a speculative context – the persistent threat to democracy presented by political entropy, the aesthetic, philosophical and metaphysical properties of mathematics, the social and political impact of ends versus means – yet none of these themes are allowed to develop beyond their importance to what is finally a familiar plot based around one individual’s quest for power, freedom, or absolution, take your pick. If the characters had been more complex, more fully realised, I would have been happier to accept a more formulaic plot. But Lee’s characterisation – like his sense of place – is sketchy at best.

I can see why SF readers might enjoy this book – indeed I rather enjoyed it myself, especially towards the end – and there is certainly material for discussion here. But I don’t personally understand what marks it out as ‘best’. What would it look like as a winner in ten years’ time? I would think, for all its decorated surfaces, surprisingly conventional.

*

Nina Allan is a writer and critic. Her debut novel The Race was a finalist for the British Science Fiction Award, the John W. Campbell Memorial Award and the Kitschies Red Tentacle. Her second novel The Rift will be published by Titan Books in July 2017. She enjoys arguing about books in general and science fiction literature in particular, and makes these arguments public from time to time at her blog, The Spider’s House. Nina lives and works in Rothesay, on the Isle of Bute.

>> Read Nina’s introduction and shortlist.

11 Comments

-

for all the information we are given about buildings, rooms, planets, spacecraft, cities, landscape, the action may as well be taking place inside a games console

I took that as a deliberate choice, and to me it’s one of the traits that most convinces me that Lee is following in Iain Banks’s footsteps. Banks’s novels were also characterized by a sort of semantic detachment, which in its best moments drove home the point that while many of the events they described happened in settings that would be completely alien to us, their significance and implications were often universal (the example that always comes to mind is the troupe of soldiers slowly advancing towards a target, who are revealed to be micron-thick worms moving between giant slabs of undersea ice). I don’t think Lee pulls this trick off as well as Banks (though I think it might be fairer to compare Ninefox Gambit to Consider Phlebas, another book that tries to use an outsized body count to make an anti-war point that would have been better served by a less sensationalistic approach), but it certainly feels intentional to me.

-

Hi Abigail,

I think I tend to agree with you on the matter of this being an informed choice on Lee’s part. I can’t comment on the comparison with Banks because I simply don’t know the ‘M’ side of Banks’s oeuvre well enough, but the matter of intent was on my mind a lot while reading 9FG. I did assume that Lee was streamlining description deliberately – why would characters moving within a deeply familiar environment bother to keep describing that environment, or even notice it? – but for me this strategy was ultimately unsuccessful because too much had been pared away. I was left wanting a greater sense of place.

I think 9FG would have worked better for me on these terms if Lee had gone deeper into the maths, played fully to the book’s strengths and made it even more abstruse! As things stand, we have neither sense of place nor in-depth exploration of the core ideas. Both would have been magnificent, either would have been great. I guess I just wanted more than the standard MilSF plot template.

I have become rather fond of this book over time though – much more so than a couple of the others! I admire its ambition, even if that ambition does not feel fully realised.

-

Thinking about this some more, surely the vagueness of the setting is also related to the central mathematical premise? How can you describe a world completely when the very fabric of reality is contingent on the calendar you follow, and can be changed by it in an instant? When I wrote about the book last year, I took the idea of the Hexarchate imposing calendrical discipline, and ruthlessly rooting out “heresies”, as a metaphor for cultural imperialism, but thinking about it, the metaphor runs in the other direction as well. It’s a reminder that many of the things we take as immutable facts of our existence are in fact decisions made by those in power (often a long time ago), and have no meaningful, concrete reality except the consensus that has accumulated around them.

-

That’s an interesting interpretation, but I’m not sure the book really backs it up. One of the things that disappointed me about the novel (whose central conceit I really liked, whether you classify it as fantasy or alt-universe physics) is that there is very little feel for how changes in the calendar actually affect things. The only real discussion I recall involves the effects on military formations and weapons, and how no one wants to be restricted to calendrical-invariant weaponry because the exotic, calendar-specific weapons tend to be more powerful. I didn’t come away with any real feeling for what would be different under the calendar adopted by the heretics of the Fortress of Scattered Needles (only that the instigators believed they would benefit). For my tastes, I thought the novel would have been strengthened if it had made some of that reality-alteration more concrete.

-

-

“why would characters moving within a deeply familiar environment bother to keep describing that environment, or even notice it?”

Surely that depends on how safe that environment is? If you are in a war, you would be hyperaware of even the most familiar things because you would be checking for danger or looking for shelter or just making sure that it is still as it should be. Every personal account of wartime experience I have read is full of vivid descriptions of the environment, whether it is strange or familiar, a lot of the time because you don’t know whether this will be the last thing you see.

One of the reasons I’m suspicious of the comparisons with Banks is because he caught this sense. The more peril his characters face, the more they are aware of what is around them. So for me the absence of any sense of environment would imply the absence of any real danger.

-

“So for me the absence of any sense of environment would imply the absence of any real danger.”

Not getting a ‘soldier’s eye view’ is indeed part of the problem. Because the narrative is mainly concerned with the top brass – those who are meting out danger on a grand scale but are only rarely personally caught up in it – there is always that sense of distance. Again, this could be intentional, but the end result leaves you constantly at one remove.

-

-

-

-

– “What’s it like to be a simple soldier in the armies of the hexarchate?”

There are quite a few scenes which cut to the simple soldiers and the squaddies-eye view, and although they deliberately don’t foreground it, the horror that is the Kel formation instinct comes through in them. I would certainly have liked to see more – and also some sense of ordinary life away from the military – but I think that Lee does try to answer this question.

– “After reading more than three hundred pages I am still unable to decide if the Fortress of Scattered Needles is a vast space station, an artificial satellite or a fortified garrison on an outlying planet.”

It’s a vast space station. Seemed clear to me, but YMMV.

I think everyone who I’ve spoken to about this book mentions that they had some difficulties as it opens – there are some very strange concepts being presented without much external comment – and I certainly had to stop and readjust my mindset after a few chapters.

On my recent second read I found the elements of the horrors of war you say are slightly lacking to be much more evident than on my first time through. They’re quite understated, because as most of the characters are unable to objectively examine the waters in which they swim we don’t get much high emotion from them about it, but I was unable to miss the sense of horror at the things various characters accepted through their chemically-induced stoicism.

Were someone to be foolish enough to put me on a jury of some sort, I would be arguing for the inclusion of fresh new voices who do something different and startling with old tropes, and Ninefox Gambit would be just the ticket, so I personally see it as an excellent entry in the Clarke shortlist.

-

Nina, you have missed the point of my novel entirely.

Pingbacks

-

[…] “A Night at the Opera: Ninefox Gambit by Yoon Ha Lee: a review by Nina Allan” […]

-

[…] Ninefox Gambit: by Yoon Ha Lee: a review by Nina Allan [The Anglia Ruskin Centre for Science Fiction and Fantasy] […]

-

[…] the narrative vision of the dizzyingly inventive and vividly imagined Ninefox Gambit, a military-space-opera with more than a few unexpected twists and turns. In Yoon Ha Lee’s unrecognizably far-future […]