By Paul Kincaid

Good Morning, Midnight — Lily Brooks-Dalton (Wiedenfeld & Nicolson)

I still haven’t reviewed two of the books on my original shortlist. As it happens, we now know that neither of the books made it onto the Sharke Six, and neither made it onto the official Clarke Award shortlist, though I suspect for rather different reasons. So I thought I would take this opportunity to consider why they might not have been chosen.

I still haven’t reviewed two of the books on my original shortlist. As it happens, we now know that neither of the books made it onto the Sharke Six, and neither made it onto the official Clarke Award shortlist, though I suspect for rather different reasons. So I thought I would take this opportunity to consider why they might not have been chosen.

I’ll start with Good Morning, Midnight by Lily Brooks-Dalton.

Superficially, this seems to be exactly the sort of novel that has often found its way onto the Clarke shortlist. It is an elegantly, at times beautifully written novel, as here when an astronaut moves from the spinning outer ring of a spaceship to the gravity-free core:

[She was] climbing up the exit node’s ladder, her protein bar clamped between her teeth. After a few rungs she felt the weight slip from her body and she let go, kicking off to float the rest of the way. A few crumbs detached from the bar and drifted in front of her. She snapped them up like a hungry fish and propelled herself down the greenhouse corridor. She grabbed an overhead rung to stop herself in front of one of the tomato plants, where she rubbed a few leaves between her fingers, releasing the smell into the air.

Pretty full of mainstream literary sensibility, isn’t it? There’s the compelling imagery, “like a hungry fish”; there’s the sensuality, the smells and textures of the passage. Of course, it’s not altogether convincing. Would the transition from artificial gravity to free fall be quite so abrupt? And how on earth does she snap at the crumbs when she already has a protein bar clamped between her teeth? But it has the polished affect of a writing school student attempting to convey the feeling of something she has never actually experienced except, maybe, on film.

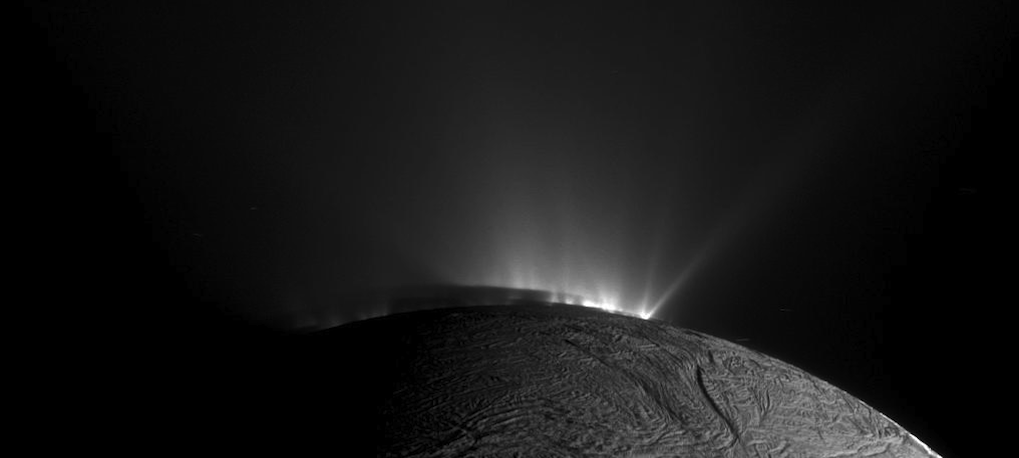

It is fine writing, and it is undeniably science-fictional, since half the novel is set on board a spaceship returning from the moons of Jupiter, while the other half is set at an Arctic astronomical post after some sort of global catastrophe. What’s not to like?

Of course, the novel isn’t about these science-fictional elements. Instead it uses these elements as an extended metaphor, or rather two extended metaphors that work towards the same end. But then, along with satire, metaphor is one of the most common uses of science fiction: we read about the future as a way of reading about today. So far I have said nothing against the novel, nothing that differentiates it from numerous other literary meditations on science-fictional themes that have been shortlisted for the Clarke Award in years past.

Except that the metaphor is facile and flaccid and disconnected from any sense of reality. Science fiction as metaphor works best when the science fiction itself is made as real, as substantial as possible. We immerse ourselves in something convincing, and the resonances with our own external world ring that much louder. That, however, is what Lily Brooks-Dalton does not do.

In two alternating narratives we are hammered over the head with images of loneliness and messages about the need to connect with other human beings as the way to complete our own humanity. Worthy stuff, of course, but that is all it is: a message, not a fiction.

In odd-numbered chapters we are introduced to Augustine, an old man now, 78, at the end of a long, distinguished but solitary career. He is stationed at an astronomical research establishment in the Arctic Circle. Before the novel opens, everyone else at the establishment was evacuated because of rumours of war. Augustine chose to stay on: he has no connections, no family, nothing to go back to. Besides, the isolation suits his personality.

Except that he is not alone. No sooner has the last plane carried away the last of his fellow researchers than he finds a little girl hiding out in one of the buildings. A little girl who happens to have the same name as the daughter he abandoned before she was even born, the daughter he has never seen. Now we have all read enough of this type of story to recognise right away that this impossible creature isn’t a real little girl, she is a figment of his imagination, an externalization of his psyche, someone he can talk to in his solitude and a trigger for his memories. Which is exactly what she proves to be.

Thus, in among the familiar trials and tribulations of life in the Arctic spring – encounters with wolves and polar bears, breaking ice, accidents and illness – we get long memories. There’s an unhappy childhood, a brilliant career, an inability to relate to other people, a constant movement from remote location to remote location whenever friendship looms, a solitary love affair that he abandons the moment the woman falls pregnant, a belated attempt to connect with the daughter he has not seen by sending her expensive birthday presents until they move without a forwarding address. He is very quickly revealed to be a prick and a prig, but, of course, at the last the imaginary girl humanizes him, as she was always meant to do. And all of this takes place within the hermetically sealed Arctic whiteness of his mind.

There is a type of story in which some avatar of the writer is isolated within a white room and encounters various fragments of memory and imagination; think of books like Mantissa by John Fowles or Travels in the Scriptorium by Paul Auster. I suspect they are fun to write, but they are rarely as much fun to read because of the lack of detail, the lack of substance. And the story of Augustine follows pretty much the same script. Because everything is sealed within his mind, there is no connection with the outside world. In fact, the outside world has conveniently gone away. That war, whatever it was about, whoever it involved, however it was fought, has served to chop reality out of the picture. Augustine has no communication with the outside world, but otherwise the war has not affected him in any way.

Against the sterility of Augustine’s story, we encounter, in even-numbered chapters, the story of Sully. Mission Specialist Sullivan is one member of a six-person crew aboard the Aether. They have just completed the first manned exploration of the moons of Jupiter. It was a tremendous success, they have made great discoveries, and now they are on their way home.

Their elation is dampened by the fact that all communication with Earth has suddenly ceased. With no warning, no hint of anything untoward, they find there is no one on Earth to talk to, no one who will talk to them. Later, as they near journey’s end, they see that there are no lights on the night side of Earth. This is the same war that isolated Augustine, but still we know nothing about it. There is no trace of radiation, no indication of any known weapon being used, but abruptly at the flick of a switch the whole of Earth was rendered lightless, powerless, perhaps lifeless (except for Augustine’s tiny fragment of Arctic ice).

Let’s be clear, this is not a fully thought through scenario, it is not a scenario in which the author has any interest whatsoever, it is simply an authorial convenience that allows her to isolate her characters and play out her metaphors. And aboard the Aether the story quickly becomes one of despair, depression, recriminations. I am sure the emotional response in such circumstances would be much as we’re shown here, but I am also sure that there would be concerted attempts to find out more, communication equipment would be checked and rechecked, plans would be made for the simple necessities of what would happen once they arrive back in Earth orbit.

The trouble is that Lily Brooks-Dalton has written a novel about the emotional reactions to isolation. She hasn’t paid any attention to the circumstances of such isolation (the off-stage war makes no sense whatsoever), not to the practical responses, the way people might behave as well as feel. None of the characters in this book are people who enquire, they are people who simply reflect. They could be locked in a bare room and the novel would change not one iota.

In short, this novel is science fiction simply because the artifice of science fiction is a convenient way of setting up the metaphor. There has been no attempt to think through that artifice, to establish the solidity of the situation in which the metaphor acts. Consequently, there isn’t enough substance in the novel to warrant its consideration for a science fiction award.

*

Paul Kincaid was one of the founders of the Arthur C. Clarke Award; he served as a judge for its first two years, and administered the Award from 1996 to 2006. He co-edited The Arthur C. Clarke Award: A Critical Anthology with Andrew M. Butler. He has contributed to numerous books and journals, and is the author of two collections of essays and reviews: What It Is We Do When We Read Science Fiction and Call And Response. His book on Iain M. Banks is forthcoming from University of Illinois Press. He has received the Thomas Clareson Award from the SFRA, and the Best Non-Fiction Award from the BSFA.

>> Read Paul’s introduction and shortlist.

2 Comments

-

My inner pedant cannot be deterred from pointing out that there aren’t any astronomical observatories in the Arctic, what with the dreadful weather and horrible observing conditions. (Antarctica is another story, but it has very different climatological and meteorological conditions from the Arctic.) Also, you’re quite correct, the change in gravity would be nothing like the way it’s described.

I don’t insist on perfect scientific versimilitude in a novel, especially when it isn’t the main focus, but this sort of “I can’t be bothered to research even the most basic details of the setting” failing is the sort of thing that would cause me to fling it across the room, if I were the sort of person who flings books.

Pingbacks

-

[…] Good Morning, Midnight by Lily Brooks-Dalton: a review by Paul Kincaid […]