Gather the Daughters by Jennie Melamed (Tinder Press)

On a small isolated island, there’s a community that lives by its own rules. Boys grow up knowing they will one day take charge, while girls know they will be married and pregnant within moments of hitting womanhood.

But before that time comes, a ritual offers children an exhilarating reprieve. Every summer they are turned out onto their doorsteps, to roam the island, sleep on the beach and build camps in trees. To be free.

At the end of one of such summer, one of the younger girls sees something she was never supposed to see. And she returns home with a truth that could bring their island world to its knees.

It has been short-listed for the 2018 Arthur C. Clarke award. A selection of our panel of shadow jurors respond to the novel below…

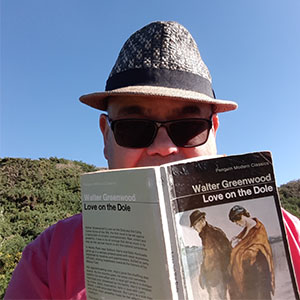

Gary K. Wolfe

As with Sea of Rust, I’d seen a few reviews of Gather the Daughters when it was published last year, most of them describing it as a feminist postapocalyptic dystopia and making the inevitable comparisons to The Handmaid’s Tale (which has joined Nineteen Eighty-Four as a go-to benchmark for critics who have read only a handful of dystopian novels). But Helene Wecker, in her cover blurb, also invokes Shirley Jackson, and in fact Melamed’s novel has more in common with stories like “The Lottery” or Margo Lanagan’s “Singing My Sister Down” (though it lacks the chilling slow burn of the former or the arresting strangeness of the latter). My own reaction to it is that it’s neither a true dystopia nor necessarily postapocalyptic; instead, it’s a horror story about a brutally misogynistic patriarchal cult, founded by ten men some generations ago and organized largely around the ritualized abuse of girls and women. The ostensible rationale for all this is something called the “scourge,” which left the mainland—and presumably the whole outside world—as a constantly burning, mutant-infested wasteland. Nevertheless, a select group of men called wanderers periodically make forays into the wastelands to bring back supplies, and in the case of one nonconforming father, books.

But almost from the beginning, we’re given unsubtle clues that the wastelands may not be what local legend claims; artifacts brought back show no signs of damage from fire, and when the occasional new arrival is asked about the fires, the response is a surprised “Fires?” I hope that’s not a spoiler, and I hope that the question of whether the wastelands are really wastelands at all—raised explicitly late in the novel—isn’t meant to be a plot twist, because I can’t imagine it surprising anyone by that point. It may well be that something bad happened to the world, but since all we learn about it is what is available to the four teenage viewpoint characters, either through local legend or what they can occasionally weasel out of adults, everything is up for question. We have no idea whether some sort of dystopian government might exist outside of this isolated community, but there’s not much evidence of it, nor is there much evidence that the outrageously misogynistic belief system handed down by those old patriarchs (and embodied in a rather crude tract called “Our Book”), is shared or endorsed by anyone beyond the local island cult. (If there is an outside government, the question arises as to why it would tolerate this survivalist nightmare.)

But even if Gather the Daughters isn’t a full-scale, government-sponsored, systemic and bureaucratic Handmaid-style dystopia, Melamed takes advantage of some familiar dystopian techniques, such as the fundamentalist minister (in this case Pastor Saul) who rails on about the evils of the old world in exactly the same terms that postapocalyptic pastors have been railing at least since Leigh Brackett’s The Long Tomorrow (by now, I’d imagine that writing these anti-intellectual fire-and-brimstone sermons should be the easiest part of any dystopianist’s job). People are mysteriously disappeared, and a ferryman who might be able to reveal secrets about the mainland has had his tongue cut out. Even Fahrenheit 451 is evoked in one chapter in which a new arrival questions the usefulness of owning any books, or of educating women at all. Some of the adult women (including that new arrival’s wife) express the programmed, defeated passivity of Stepford Wives. Every community member’s life is planned from birth; in the case of girls, this means serving as backup sexual partners for their fathers until they reach puberty, after which they’re quickly married off to bear children and then, once the children are off, voluntarily die. And, as in nearly every dystopia, there’s one brave soul who questions the system and pays for it.

The grim nightmare of Melamed’s vision is unarguably powerful, and the horror of several passages is viscerally effective (though at other times the language sometimes slips into incongruously flowery prose). What really sustain the novel, and what in my mind make it a reasonable awards candidate, are the quite distinct personalities of the four principal viewpoint characters, all teenage girls, who try to develop strategies for survival while facing an unremittingly bleak future and trying to negotiate with their own bodies: Vanessa, whose father is a wanderer who brings back books from the wastelands and selectively allows her to read them; Caitlin, the only one not born on the island (but who remembers nothing of her earlier life) and whose drunken father is excessively abusive even by the standards of this community; Amanda, married and pregnant at 15 and whose father may be the creepiest of all; and Janey, who starves herself to postpone the inevitable “summer of fruition” and who eventually tries to organize the other girls in a kind of futile resistance. Janey is the closest the novel comes to the familiar doomed-rebel-in-dystopia archetype, but she emerges as the strongest character in the book, while Vanessa’s abiding curiosity about those books gives her something of the quality of Fahrenheit 451‘s Montag. Even a couple of the male characters, such as Vanessa’s dad, display a measured degree of ambiguity, though hardly enough to exculpate them from the system they’ve bought into.

But while Melamed’s characters are strong, the cult-like community they live in doesn’t really require the resources of SF at all, and doesn’t get many. It’s not too much of a stretch, given what we’ve already seen about cult behavior (not to mention the disturbing tolerance of many Americans for casual brutality), to imagine such a community setting itself up on an island right now, and warning its residents to ignore fake news from the mainland. That’s why I think the comparisons with Shirley Jackson—not only “The Lottery” but related tales like “The Summer People’—or even Margo Lanagan or Brian Evenson, seem more apt than with Atwood or the more mainstream dystopian tradition.

Nick Hubble

Most years I find myself enjoying much more than expected a book that I most likely wouldn’t have read other than for the fact that it is on the shortlist. Of course, part of the point of the award is to encourage people to read more SF but I’m not just talking about the satisfaction of expanding horizons or completing the list before the award is made (something that has only really been viable for most readers over the last couple of years). If you are a reader – and I identified as a reader long before I thought of myself as a fan, academic or critic – then you live for those books that transport you into a another world that you can immerse yourself into and experience in what seems to be an intensely personal way. As a child, the fiction that moved me in these ways tended to involve talking animals or magical beings such as elves and hobbits. I’m still very partial to those kinds of stories but as you get older, your range extends – in my case, via vets, naval heroes and dodgy neo-Victorian military men – to countercultural outcasts and anarcho-communist artificial intelligences. Then you get your PhD and find yourself subverted by too much exposure to the work of Virginia Woolf and Joanna Russ. But, if you are a reader, that doesn’t mean that you no longer enjoy fiction; you just enjoy it differently.

The point I am trying to make is that, as a reader, I really enjoyed Gather the Daughters and felt a greater level of emotional engagement with the characters than most of the rest of the shortlist. Whereas, if the novel hadn’t been on the shortlist, I wouldn’t have heard of it and even if I had by chance picked it up in a bookshop, the cover-quote promise of ‘The Handmaid’s Tale crossed with Lord of the Flies’ would probably have sent me running. Perhaps it is not surprising that a small enclosed (in this case on an island) patriarchal society should provide a good setting for a novel; it is a pretty common format for fiction written in patriarchal societies. It is certainly no surprise to see this society represented (in an imaginative, beguiling and disturbing manner) as flawed and oppressive. However, the point of the novel is not simply that patriarchal society is flawed and repressive but also that patriarchal society is only one small ‘island’ (model of social organisation) among an almost infinite number of possible islands. This complex structuring idea allows Melamed to give the reader both of the types of enjoyment I discuss in the paragraph above. We engage with the island story of Amanda, Janey and the other girls – equally aware of the continual threat of sexual violence directed at them and of their struggle for agency – but we are also drawn in to an almost metatextual argument concerning the very inadequacy of this type of ‘enjoyable’ dystopian story that we are being told so well. (There are spoilers in my last paragraph so you may wish to skip it if you have not read the novel yet).

There is a discussion as to what is speculative or science-fictional about this novel. On the one hand, it looks and feels just like a post-apocalyptic dystopia, but, on the other hand, as the reveal at the novel’s end makes clear, it is no such thing. The fact that outside society hasn’t ground down to a halt serves to accentuate the horror of what has gone before in the story. However, it is the twist, itself, which is truly in the tradition of the finest SF. Gather the Daughters suggests to us how the very idea of post-apocalyptic dystopia is problematic and in effect a key component of the ideological structure of patriarchal society. In other words, the general message of post-apocalyptic dystopia which depicts complete societal collapse, such as The Road, is that it is easier to imagine complete Armageddon than any viable social alternative to existing American society. For me, the value of Melamed’s novel lies in the way that it calls this tendency out. It rejects the post-apocalyptic story it tells so well and directs its readers back to the complexities of the modern world. Of course, what we really needs are more stories of that modern world but Gather the Daughters takes a welcome step in that direction. It may not do quite enough to win the award (although I assume it is in contention in the judges’ discussions) but its inclusion on the list certainly marks out Melamed as a name to watch for the future.

Alasdair Stuart

Jennie Melamed’s debut, Gather the Daughters, is set on a small isolated island. A tiny handful of families live there, huddled against the elements and against the Wastelands. All the children on the island know is that this is the only place they can live. And, they suspect, there is something terribly wrong with it. When girls undergo the summer of Fruition they are married off and expected to have children. Women who’ve had two children kill themselves so others can take their place. The world turns and, slowly, surely, turns in on itself.

This is a novel defined by growth held in check. The island community, with its enforced laws and sinking church, is a tiny environment that has already been outgrown by many of the book’s leads. Vanessa, the daughter of one of the Wanderers who ‘find’ things and people in the Wastelands has devoured her father’s library and wants more. Caitlin, who survives her father’s abuses with the weary determination of someone who has endured abuse for sustained periods just wants to be left alone. Janey, who has starved herself to prevent puberty and made it past her 17th birthday. All of them and their friends and relatives are massive, expansive personalities who have the exuberance and curiosity of island kids mixed with the desperation of believing they are the last people left. All of which is seasoned with a child’s total belief in their parents.

And all of which is revealed to be a lie. As the girls go through their latest Summer, Melamed peels away the layers of the island and shows it to us and her characters alike. The ritualization of incest and abuse, the bovine platitudes of men convinced that they’re doing the right thing precisely because of how little they consult others. The women who see their daughters rise and know that on this island that will only be so far. The girls who refuse to be stopped. The novel slowly tips over into something approaching war as the two sides clash and, inadvertently, the truths of the island are revealed. The result is defiantly, undeniably science fiction even if the surviving girls, and the reader, are denied absolute certainty. This is a story about the end of a world, built into a colossal structure of arrogance, entitlement, short-sightedness and horror. Other critics have noted that Melamed seems to have a lower opinion of humanity than is warranted. I don’t.

A lesser novel would revel in that horror and cynicism. Melamed calmly dissects it all, giving us and her characters a chance to understand this world even as we recoil from it. What she denies us is simplicity. The rebellion and its consequences do not lead to the cathartic release you’d expect and desperately want. The characters are revealed to be more nuanced and subtle than even the earlier stages of the book have shown us. The ending, the island in tatters after a viral outbreak, piles tragedy on tragedy and leaves, oddly, with the survivors in a similar situation to the end of Water & Glass. However, there, there is hope for the future. Here there is hope for an eventual absence of horror.

Gather the Daughters is an extraordinary achievement, especially for a debut novel. Seething with rage and compassion, this is a definitive, uniquely voiced dystopia that needs to be read.