By Nina Allan

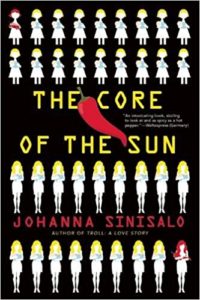

The Core of the Sun — Johanna Sinisalo (Grove Press UK)

*

Night after night I lie awake, nothing but the Messages to distract me from my clamouring thoughts. chastity-ruth says thinking too much robs you of your beauty. No man will ever want a companion who thinks too much. I do try to be more controlled. I try to shape my mind into nothingness, but when night falls in the dorms the demons stir, their eyes flashing white in the dark, looking for something to feed on.

(From Only Ever Yours by Louise O’Neill)

We awaken in a contemporary alternate Finland, a country whose path diverged from its realworld twin’s shortly after World War One. We discover that Finland is now a eusistocracy – all for the best in the best of all possible worlds – separated technologically and politically from the ‘hedonistic democracies’ of the rest of Europe and forging its own path to racial purity, social stability and material content. In this new Finland, a systematic program of eugenics has been implemented in order to reinstitute traditional gender roles and relieve the increasing psychological and social tension that has been the inevitable result of female emancipation:

We awaken in a contemporary alternate Finland, a country whose path diverged from its realworld twin’s shortly after World War One. We discover that Finland is now a eusistocracy – all for the best in the best of all possible worlds – separated technologically and politically from the ‘hedonistic democracies’ of the rest of Europe and forging its own path to racial purity, social stability and material content. In this new Finland, a systematic program of eugenics has been implemented in order to reinstitute traditional gender roles and relieve the increasing psychological and social tension that has been the inevitable result of female emancipation:

Society no longer rids itself of weak individuals by means of a natural instinct for self preservation, demanding that the weak make way for the strong. The preservation of our species thus must be ensured by other means, the nearest at hand being the prevention of the birth of weak individuals.

In the new Finland, the population is categorised and registered according to four specific gender denominations: mascos (basically men as we know them today, ha ha), femiwomen (physically fragile, naturally nurturing, sexually attractive women with great make-up and fluff for brains), minusmen (we don’t know much about them except that some of them are keen on growing houseplants) and neuterwomen (any woman who prefers trainers to high heels). Femiwomen are colloquially known as elois, and neuterwomen as morlocks, a humorous borrowing Sinisalo justifies by explaining the terms as popular slang derived directly from the fiction of H. G. Wells. Gender designations are finalised at the age of six, largely through a series of tests in which girls are tested for blondeness and tempted with toy trucks. Once categorised, femiwomen will go off to eloi college to learn about home economics and prepare for the mating market, while neuterwomen are compulsorily sterilised, raised in morlock homes and prepared for a hard life of toil as lavatory attendants or farm workers.

The mascos do all the things they presumably do in the real Finland, only with infallibly supportive, cosseting wives by their side and the state’s permission to be as shitty and macho in their day-to-day dealings with them as each personally finds fit. Again, we don’t learn a whole lot about what minusmen do – run flower shops, presumably – or whether they’re allowed to breed or not. They don’t have an ironical Wellsian moniker either, poor things.

The story follows the lives of two sisters, Vera and Mira, raised by their grandmother in the countryside and whose fates radically diverge as they come of age. Renamed Vanna at her official registration as an eloi (women aren’t allowed to have the letter ‘r’ in their name, for reasons I either missed or that weren’t specified), Vera is in spite of her beauty a secret morlock: she prefers the toy fire truck to the dolls, she learns to read early and well, she has no desire to become a nurturing, submissive wife and mother. She nonetheless must learn to behave as an eloi, or risk exposure and conviction for gender fraud. Manna on the other hand is a textbook eloi: sweet, insatiably curious in an unthreatening, kitten-like way, obsessed with attracting a mate. When the man she falls for, Jare, seems more interested in her sister, Manna makes the disastrous mistake of marrying the abusive and generally untrustworthy Harri.

A little over a year later, Manna disappears. Vanna is devastated. She blames herself for the tragedy and enlists Jare’s help in getting Harri sent to prison for murder. Meanwhile, she becomes a key player in Jare’s secret plan to raise sufficient funds to purchase visas and leave the country. With his modest earnings as a farm worker being insufficient to this task, Jare has become involved in the underground world of prohibited substances. All stimulants are banned in the new Finland: not just alcohol and tobacco but caffeine too. Even chocolate is dodgy and has to be obtained on prescription. Worst of all is the chilli pepper, which has become the subject of dangerous addiction and the holy grail of an underground capso cult. The chilli and the illicit trade that governs its distribution is presented as if the substance in question were heroin or cocaine:

I didn’t even think about what exactly was meant by that veiled threat. I knew that some people who’d had dealings with chilis had disappeared. There were rumours of capsos in high places who could use their own channels to handle dealers who took risks. There were whispers about ways to get to a snitch the moment he was put in the paddy wagon. Those might be legends, but the heavy, juicy red bag was there on the table. It was real. Fresh stuff is impossible to fake.

The band of hippies who eventually set up an illegal chilli propagation enterprise at the farm believe that capsaicin is potentially the basis for far more than just a recreational drug. They aim to cultivate a super-chilli, the eponymous Core of the Sun, which will open the doors of perception and provide the stimulus for a radical revolution of mind over body – ‘take me chile, and I will Escape’ – though Vanna is initially less interested in their shamanistic theories than in their potential as a ready source of the drug to which she has become addicted.

While I can see my fourteen-year-old self loving Johanna Sinisalo’s The Core of the Sun with a heady passion, it is a source of sadness to me that, though its author is an innovative, original and acutely intelligent writer and one I admire greatly, my fifty-year-old self struggles to find a single good word to say about it.

It is interesting that Sinisalo goes into considerable detail – some factual, some imaginative extrapolation – on the medicinal properties of capsaicin and its powers as a stimulant. It is also commendable that she takes so much care in laying down a believable basis for the societal norms of the new Finland as they have become established. Through a series of embedded documents – some based entirely on factual articles on eugenics written in the 1920s and 1930s, others seamlessly presented invented extensions of these same theories – Sinisalo is keen to show how such doctrines could have been put into practice, how many of the beliefs enshrined in them still persist, how some of them continue to shape and dominate our society as it currently stands. This is all well and good and it is clear throughout that Sinisalo is keen to present The Core of the Sun as a darkly satirical, occasionally humorous vehicle for serious discussion of gender roles and the expectations still placed on girls and young women today from their moment of birth.

Why then did I find this novel so tedious, so predictable, so finally undermining of its own mission statement to give back the fire to humankind? Firstly because it’s been written so many times before. It wouldn’t take me long to compile a substantial list of novels in which ‘the wimmins’ have been separated off, farmed, traded, coerced, placed in reservations, lobotomised, forced to breed with Martians, whatever. Nothing wrong with revisiting important themes – there are only ten basic plots in all of story, etc etc – but as I suggested in my earlier review of The Destructives, if you’re going to use tried and tested tropes and make a satisfying novel out of them, you must also bring something new to the game, either in terms of outline concept, formal execution or psychological complexity and preferably all three. One could argue that Sinisalo has brought chillies to the game, which is true, but ultimately of trivial importance in a novel that owes such a heavy debt to its more radical forebears – The Handmaid’s Tale in particular – that it would have to mortgage itself three times over to have a hope of repaying.

Like Atwood when she wrote The Handmaid’s Tale, Sinisalo has rooted the foundations of her dystopia in lived reality – Atwood has famously stated that everything that happens in her fictional Gilead has already happened, somewhere, sometime, in the world as we know it. The Handmaid’s Tale succeeded and still succeeds, thirty years after it was first published, because it presents a perfect fusion of social commentary and intense, richly imagined psychological storytelling. One could easily argue for it on these terms as the perfect science fiction novel, a truly worthy inaugural winner of the Arthur C. Clarke Award.

For today’s reader and especially today’s female reader, The Handmaid’s Tale is still terrifying on all kinds of levels: in its unflinching portrayal of a brutally violent and oppressive society, in its detailing of that regime’s effect on the lives and integrity of women, in its nuanced, starkly moving portraits of individual women caught up in its appalling events.

The Core of the Sun, by contrast, shies away from anything but the most cursory contact with harsh reality. The characters are little more than placeholders, content to play their role within the narrative but little more. Nor can it be convincingly argued that it is the brutal nature of the regime that renders the characters two-dimensional. As opposed to The Handmaid’s Tale, where the reader is left in no doubt whatsoever of the fate that befalls transgressors, we are offered little more than veiled hints about the nature of law enforcement in the new Finland. There is a brief reference to someone ‘losing their head’ over some infringement or other, but this may as well be metaphorical for all the sense of tension and threat it brings to the action. Even the morlock home where one of the secondary characters is brought up is understood to be pretty dismal but basically humane. ‘There was nothing wrong with the place,’ Terhi concedes. ‘People fit to work but not to procreate have to grow up somewhere’. The novel’s ending in particular is abjectly cowardly in this regard. [Spoilers ahead] When Vanna learns that Harri did not after all murder Manna, but instead used her as a source of income to fund his gambling habit, we are given to understand that she was sold into some kind of sexual slavery. But the details – the reality – of such a fate is squirmed away from, replaced with bland generalisations that do everything to deflect attention from the horror of Manna’s personal experiences:

Oh eusistocracy.

To keep the loudest ones happy you brought a known drug into the reach of the many.

You thought you were liberating sex.

But you liberated something else.

Power.

One taste of it just leads to larger and larger doses.

Ridiculously large doses.

Incomprehensible amounts.

Sickening amounts.

Doses so large that the brain can’t comprehend them.

The mind just explodes in white light.

The fate of Manna, who is severed from her tortured existence and brought ‘inside’ her sister by the magical power of the super-chilli, has to be one of the biggest cop-outs in the whole of what purports to be serious science fiction. Even if this conclusion is meant purely as metaphor – the power of memory to keep a loved one alive – then it is rendered in such saccharine, euphemistic terms that it still sucks. The one instance of actual mano a mano violence spilling over into the narrative – the final confrontation between Vanna and Harri – is little short of cartoonish.

I’m not suggesting that the stage of a dystopia need be littered with bleeding bodies to be convincing, but some sense of actual personal danger would at least suggest to readers something of the realworld implications when loathsome theories are put into practice. What we have here is horror with its face covered, which is just cheating.

Even at the loathsome theory level – the idea of breeding submissiveness into women that Sinisalo based upon Dmitri Belyayev’s research with foxes – the novel’s effectiveness is questionable, because by its own rules it doesn’t make sense. The morlocks are not the ‘weak individuals’ they are purported by state doctrine to be – they’re genetically stronger, more intellectually curious, more adaptable. One understands of course that the idea is to breed only women into a state of submissive timidity, leaving men as the dominant gender and entirely in control, but it still won’t wash. By consistently weeding out the stronger women, this policy of fatally regressive eugenics would soon impact on the men as well, resulting finally in a nation of femiwomen and minusmen, unable to adapt to adversity or fend for themselves and thence vulnerable to extinction or (if we want to take this in any way seriously) invasion from neighbouring countries seeking more territory. In other words – and let’s not sugar-coat this – it’s bollocks.

I became increasingly frustrated with this novel as it progressed. As science fiction it seemed to me facile, dated, superfluous to requirements. As a work of literature it felt intellectually shallow and emotionally unsatisfying almost from the first.

At a sentence level, conversely, there were fewer weaknesses. Sinisalo’s clear and clever turn of phrase, her pleasure in language, her gallows humour, her willingness to play with form – these were all evident, at least to an extent, and it was this clash between Sinisalo’s continuing thoughtfulness and overall competence as a writer and my own strident disappointment with the results that led me to question whether I was the intended audience for this book at all.

Is The Core of the Sun perhaps intended as fiction for younger readers, readers encountering the issues it raises for the first time and who would therefore be less bothered by the over-familiarity of the themes, more receptive to the straightforward good versus evil power dynamic, more caught up in these insipid characters and their too-tidy fates? In other words, could Sinisalo’s novel be better described – and function more effectively – as YA?

I would have liked to think so, because I admire Sinisalo, but I cannot help admitting that even as YA – indeed especially as YA – The Core of the Sun has problems. Here we have a critique of sexism that enthusiastically reinforces the highly questionable ‘tomboys clever, girly-girls stupid’ stance, a viewpoint that is dated, divisive, othering, and in its cumulative repetitiveness here ultimately almost as tiresome as its reverse. The idea that enjoying clothes and make-up and an afternoon of gossip with your girlfriends are signifiers of lower IQ and ‘bad feminism’ now seems older than the ark and personally I’d be hesitant about recommending the text to younger readers on those grounds alone.

It gets worse, though. There were passages I found troubling in their tendency to fall back on other dated stereotypes and caricatures:

The mascos dressed as elois on the TV shows tittered and giggled and fluttered and swung their hips and stuck out their lips and used an exaggerated caricature to show how an eloi would look and sound. I had read in one of Aulikki’s books that in old American movies, white people painted their skin black to portray negroes. I wondered if some dark-skinned people who watched those movies thought that they were supposed to speak in simple sentences and roll their eyes and be childish and superstitious.

This passage skirts dangerously close to the ‘ridiculous ugly transwoman’ narrative, and referencing blackface in respect of it only makes it more problematic. The following is also pretty dubious:

Mirko strikes a noble pose, and as I look at his long dark hair and hooked nose, I can’t help thinking that he looks less like a Finn than a mythical ‘noble savage’, a wise, brave, mystical member of the original Native American race, I wouldn’t be surprised if his inclinations toward earth-based spirituality were something inspired by growing up looking like that.

Still more discomfiting than these isolated slip-ups is what the novel finally has to say about gender roles and ‘what women want’. Sinisalo’s decision to make Vanna a ‘passing’ eloi rather than a designated morlock seems doomed to lead this novel into places where it’s bound to flounder. Here we are at the debutantes’ ball, where Vanna and Manna are first presented as sexually mature females and thus ready for mating. Vanna has dressed down in an attempt to let her sister – still heartbroken over being rejected by Jare – be the belle of the ball. But her efforts misfire:

In this carnival of peacocks and puppets, things went absolutely the wrong way. I did stand out from the crowd. But I stood out like a graceful white gull soaring among a flock of fluttering, cawing, scratching birds of paradise piled with plumes to the point of collapse.

I spent the whole evening on the dance floor, though I’m a bad dancer.

Cinders, you shall go to the ball, even though you are a verily a morlock and above such things. Personally I find it disappointing that both our morlocks, Terhi and Vera, end up yearning for stable male-female partnerships just like the average eloi, that Vera can only overcome her chilli addiction once she enters a throbbingly satisfying sexual relationship with a man. There’s not even a hint that other kinds of relationships might be equally fulfilling or even possible.

I remember when Sex & the City first came on TV, how it was heralded as a bold, provocative look at female emancipation at the dawn of the new millennium. You watch it, you enjoy it even (I know I did) but there’s no putting off that moment when you suddenly realise the entire series has been directed towards one woman’s search for the perfect male and the perfect home. I hate to say it, but for all its feminist posturing, The Core of the Sun ends in pretty much the same place.

For me, this is precisely the kind of clompingly unsubtle narrative that gives so much generic science fiction a bad name and it’s not particularly brilliant or era-defining as young adult fiction either. Though it pushes a number of apparently requisite buttons, The Core of the Sun is mildly entertaining satire at best and I would be disappointed – although not remotely surprised – to find this book turning up on the official shortlist.

*

Nina Allan is a writer and critic. Her debut novel The Race was a finalist for the British Science Fiction Award, the John W. Campbell Memorial Award and the Kitschies Red Tentacle. Her second novel The Rift will be published by Titan Books in July 2017. She enjoys arguing about books in general and science fiction literature in particular, and makes these arguments public from time to time at her blog, The Spider’s House. Nina lives and works in Rothesay, on the Isle of Bute.

>> Read Nina’s introduction and shortlist.

7 Comments

-

“One could argue that Sinisalo has brought chillies to the game, which is true…” That truly made me laugh.

I am going to have to digest your thoughts on this, Nina, but here’s what I’m thinking right now. I think I see two major arguments you have against this book: one, that it’s overtly binary (esp. for a setting with four genders)–though I think that’s due in part to the social setup (but some unprescribed behaviors from the eloi sister would have made things more interesting and necessary, I agree)– and two, that it doesn’t feel dangerous enough. Being a lipstick-wearer myself, I agree with the first argument, although I do remember thinking how more modern it feels compared to other dystopias from feminist writers because it addresses gender rather than sex (although, looking back at your very convincing argument, I’m not so sure I feel that way anymore). Regarding the other argument, what I most appreciate about the novel was just how insidiously gentle the entire set up is (although the initial legislation to get to this point is a bit hard-to-swallow), rather than with something like The Handmaid’s Tale, where everything is so suddenly different and evil. The Core of the Sun in many ways feels very much like our own society–going back to my own “is this even fiction?” comment– which is what I think Sinisalo is trying to harness.

Regarding your point about the bollocky science: ha, yes, very good point. And that its superficial, unambiguous design feels more like YA: yes, definitely.

-

Hi Megan!

I wouldn’t normally have started in on the science as that always feels like a pretty cheap shot to me, especially with a novel like this, where the practical application of genetics isn’t really the point. But as you’ve no doubt noticed from this review, this book and I simply did not see eye-to-eye, and the wonky science was just one more thing…

I suppose it just felt to me, more and more as I moved through the text, that a novel like this so perfectly encapsulates everything science fiction is ‘supposed to be like’ by people who in the main don’t read much SF: the lack of sophistication, the simplistic portrayals, the millimetres-thin characterisation. I felt that the novel would be blown apart by anything heftier, and could only ever function as allegory, a subgenre I’m not overly fond of, which probably goes a long way to explaining my displeasure 🙂

-

-

By consistently weeding out the stronger women, this policy of fatally regressive eugenics would soon impact on the men as well, resulting finally in a nation of femiwomen and minusmen, unable to adapt to adversity or fend for themselves and thence vulnerable to extinction or (if we want to take this in any way seriously) invasion from neighbouring countries seeking more territory. In other words – and let’s not sugar-coat this – it’s bollocks.

I really thought it would be the unconvincing attempts to claim The Underground Railroad as science fiction that would overcome my chronic lack of time and prompt me to comment on a review properly but, well, here I am. It’s well over a decade since I studied genetics formally, and I am not a geneticist, but I have some geneticist friends, at least one of whom has read the novel. The short version is that genetics is weird, and that mechanisms exist by which the eugenics programme in the novel might work. The longer version…

You’re right that a straightforward dominant/recessive system (like Mendel’s round and wrinkled peas) would not work in this sex-specific fashion, because you’d always have heterozygotes messing things up. However, it’s unlikely that many of the traits being selected for work in a straightforward dominant/recessive way, since they are cognitive/behavioural.

What is needed for the eugenics in the novel to “work” is a mechanism that allows sex-specific selection of traits that are not coded on sex chromosomes. Some options:

1) If you apply sex-selection consistently enough, you can potentially select for the formation of additional sex chromosomes. That is, say that a bunch of the behavioural stuff is coded for on chromosome 15. If you consistently select women with one set of chromosome 15 genes and men with another, that could (should) eventually select for individuals in which 15(F) and 15(M) start behaving more like X and Y.

2) Alternatively, you might be selecting for traits coded on chromosome 15 that are under the control of genes on the Y chromosome. In that case, you also don’t need changes in the Y chromosome — mutations on chromosome 15 could produce sex-specific effects, and you could then selectively breed to increase the overall prevalence of that mutation in your population.

3) (This is my favourite) Ruff supergenes. In a particular bird species, several strongly divergent male phenotypes exist. They are the result of an inversion on chromosome 11, which disrupted how that chromosome would otherwise behave during cell division. Look at Figure 1 in the Küpper paper (first link) — one of the phenotypes is “independent” (masco?), one is a semicooperative “satellite”, and one is a female-mimic (“minus”?). They have very different behavioural profiles, and you could selectively breed to increase the prevalence of the rare phenotype in a way that would not affect the overall genetic health of the population. It’s not impossible to imagine a similar mechanism arising in humans.

Now, I’m not necessarily saying that Sinisalo had any of these models in mind — the macho/minus eloi/morlock division suggests that she was at least starting from the idea of a dominant/recessive model. And obviously there are many factors that could prevent these models from taking hold. But I’m reasonably sure that nothing in the book completely rules out their operation. And — here’s the thing — the fact of this possibility is what elevates the novel for me and, to Nina’s point, is what makes it effectively horrific. I remember the moment when the penny dropped that this was an actually eugenicist state, and that the state was breeding essentialism that otherwise would not exist into humans. I found that to be a really effective moment of horror, and it hinges on the genetics being within the realm of the plausible.

(I should note that there is a problem with all of the mechanisms described above: it is very unlikely that selective breeding would have the effects described in the time-frame described. Dog experiments notwithstanding, you’d almost certainly be talking thousands of years rather than a century. But that is an aspect I’m willing to handwave for the sake of the story…)

(As a footnote: the other mechanism, of course, could be that the selective breeding doesn’t work, it’s just that the government is very effective at preventing morlocks and minus men from breeding, so they just manually recreate the phenotype pools they want in each generation. Not sure there’s anything in the book that contradicts that, either.)

-

Hi Niall, great so see you here again!

These insights into genetics are fascinating and – who knows? – could provide future inspiration for a more rigorous SFnal examination of the subject, so they’re valuable in and of themselves. But as I stated in my reply to Megan, above, the whys and wherefores of the novel’s science were just a side issue for me. The main problem with The Core of the Sun is that as an act of imagining it’s insipid and unconvincing. In fact the book it brought most forcibly to mind for me was Emmi Itaranta’s The Memory of Water, a Clarke shortlistee from a couple of years back that many people loved but that I found to be similarly mealy-mouthed.

And now I definitely want to hear your thoughts on The Underground Railroad 🙂

-

Niall, thanks very much for this. I have only an interested layperson’s knowledge of genetics, so this was really helpful.

It seems that the Sinisalo and Whitehead novels are shaping up to be the most contentious among the Sharkes.

-

-

It sounds as though this novel is much less radical than I hoped it might be, despite the chill of Megan’s “Is this even fiction?” comment (especially for those of us living in the US at this particular time – not that you need to be an American to find it horrifying). Still, I think I’ll queue it up after The Underground Railroad in my TBR pile.

Pingbacks

-

[…] “Light My Fire – The Core of the Sun by Johanna Sinisalo: a review by Nina Allan” […]