By Paul Kincaid

*

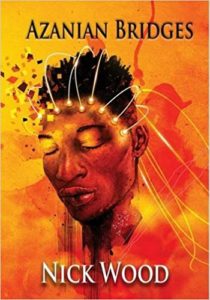

Azanian Bridges — Nick Wood (NewCon Press)

If science fiction doesn’t make us look differently at our world, then science fiction doesn’t have a point.

If science fiction doesn’t make us look differently at our world, then science fiction doesn’t have a point.

Let me unpack that. Science fiction makes changes in the world, that is one of the key things that makes it science fiction. But that change must connect in some way with how we understand the here and now. An alien in a story makes it science fiction, yes, and the author may have taken great pains to specify the greenness of the skin or the exact length of the tentacles, but unless the intrusion of the alien reflects upon what it is to be human it is little more than wallpaper. When H.G. Wells wrote about Martians invading Surrey it wasn’t a novel about Martians, but about being human in the face of that invasion, about people used to being colonisers suddenly finding themselves colonised. The way the novel looks out into the world is why The War of the Worlds is still read today.

All too often I read science fiction novels where the author has fallen in love with their own invention, where everything turns inward to explore that invention in great detail, and as a result the book becomes hermetically sealed, totally cut off from any external resonance. The mind tends to slide over the surface of such books. They can be fun to read, have their own immediate pleasures, but they are gone the moment you turn the last page.

So any novel that has rough edges because it is deliberately reaching out to intersect with the unevenness of reality is going to snag the mind and hold the attention long after the book is closed. That is what I found with Azanian Bridges. It is not a smoothly polished artefact; it is jagged, raw, awkward in places. You cannot slide over the surface of this novel, you keep getting splinters, because the book is constantly telling you to stop, think, look not into the novel but out at what the novel tells you about the world. It is not, perhaps, great literature; it has few passages that stand against some of the more awe-inspiring scenes in The Underground Railroad, for example (though that is a novel with which it demands comparison, for reasons I will come to shortly). But it is, I think, great science fiction; it is a novel that insists you look into its mirror and notice what is going on behind you.

What you see in a mirror, of course, is what you do not, or cannot, look at directly. But the distortions, exaggerations and inventions of science fiction can make it possible to see the unseeable. That is how science fiction makes us look differently at the world, and the difference is there to unsettle or challenge us, because we are looking anew and newness is always unsettling or challenging. In the case of Azanian Bridges, as it is with The Underground Railroad, that thing behind us in the mirror is race. Both novels look to the past, in part because race is one of those issues we like to pretend we have put behind us, and in part because that past continues to shape our present. Both contend that the issue of race is a fundamental failure. In the case of The Underground Railroad, the failure is social, or sociological, a failure of white America at its most utopian to build a society that can find any place for the non-white other except through oppression or extinction. In the case of Azanian Bridges, the failure is psychological, a failure of white South Africa at its most dystopian to perceive any being other than its own.

It is interesting to ponder why now; why it is this historical moment that has seen race emerge as the central issue of two of the most emotionally powerful science fiction novels of the year. But that is perhaps a question for another time, when we can perhaps look with some dispassion at how these and other novels fit into a context in which racial violence, fear and hatred of the other, have spread like a disease across Europe and Australasia, America and parts of Africa and Asia. For now let us just shudder and accept that these two books speak acutely to our present moment.

Although at first it is hard to see the present in Azanian Bridges. This is a novel that may be set chronologically in the near future, but politically and economically it is distinctly set in the past. A coup by the followers of the extreme right wing white supremacist, Eugene Terreblanche, replaced the crumbling Nationalist government of F.W. deKlerk before Nelson Mandela could be released from prison. As a result, Mandela died in prison and an even more extreme form of apartheid continues to hold sway. However, for the regime to hold on to power demands increasing authoritarianism and repression, but this has a knock-on effect on the economy of South Africa. It is now one of the world’s poorer nations; a good analogy might be with North Korea, in which the borders are closed on trade, technology and information. The only way to return to the past in terms of race relations is to return to the past in every other respect, a costly lesson that a few other governments might well learn from. Access to the internet is strictly controlled, except that clever hackers have immediately found ways around these controls, so that those people that the regime most wants to shut out of the world of information are those with the readiest access to it.

The clearest illustration of the cost of this imposed backwardness comes in one perfectly judged moment two-thirds of the way through the novel. The McGuffin that drives the plot is an invention that one of the characters has made. It’s a crude device, clumsy and awkward, but powerfully effective, so much so that both the black freedom fighters and the white security services recognise that it could be a game-changer. The device is smuggled out of the country and passed to the Chinese who now provide technological advice to most of black Africa. They are able to take apart a device they have never encountered before, reproduce it in a small, neat hand-held version no bigger than a mobile phone, and them mass-produce an improved version of the device, all within a matter of days. Nothing more vividly displays how history has bypassed a country that wants to hold on to old racist certainties.

The device, an Empathy Enhancer, was invented by Dr van Deventer, a (white, it goes without saying) psychologist at a South African hospital. It is a way for him to do his job better by providing a direct link to the mind of his patient. Naturally, this modern South Africa lacks both the technical know-how and the components to make such a device, so he has had the prototype made in America and smuggled back into the country. Time and again we see that the regime’s repression of black South Africans doesn’t exactly privilege white citizens either, and we detect a swelling chorus of discontent among their number, though as yet not enough to make them act in concert with the black majority whose day-to-day existence remains pretty much a mystery to them.

Van Deventer cannot use his device openly, but he decides to trial it secretly on one of his patients, a young amaZulu student, Sibusiso, who is suffering post-traumatic stress disorder after witnessing the death of a close friend when police opened fire on a demonstration. But in a land of such systematic repression, spies and informers flourish, and the existence of the Empathy Enhancer is soon known to others, who naturally see it as more than a therapeutic tool. To the security services it would be a way to enhance their hold over the country by ensuring that no prisoner would be able to resist interrogation. To the African National Congress, it could undermine the regime by making whites experience for themselves what it is to be black.

The ANC act first, persuading Sibusiso to steal the prototype and smuggle it out of the country. Meanwhile, the security services start coming after van Deventer. Desperate to get his prototype back, and at the same time anxious to keep it out of the hands of the security service, van Deventer finds himself being drawn into the world of the urban black, a world he had never really known existed, a world that is terrifying in its alienness.

As with The Underground Railroad, the story is not resolved, perhaps the story of black and white can never be resolved. As the novel ends, the balance of terror is still maintained between black activists who have nothing to lose and state security who can only hold on to the fragility of power by increased levels of brutality. Everyone is caught between these grindstones. That is the nature of dystopia: there are no innocents, only victims. What Nick Wood does in this debut novel is show that the apartheid state, a state that held power from 1948 until 1994 in our history, a state whose shadows and echoes can be discerned in many other places still today, truly is dystopia. And dystopia destroys those who hold power as much as it destroys those the state seeks to repress.

Azanian Bridges is not a perfect novel: it is crudely structured in places, light and dark are painted with too broad a stroke. But it is a powerful novel, with an emotional kick at the end that makes it unforgettable. The world cannot be the same afterwards.

*

Paul Kincaid was one of the founders of the Arthur C. Clarke Award; he served as a judge for its first two years, and administered the Award from 1996 to 2006. He co-edited The Arthur C. Clarke Award: A Critical Anthology with Andrew M. Butler. He has contributed to numerous books and journals, and is the author of two collections of essays and reviews: What It Is We Do When We Read Science Fiction and Call And Response. His book on Iain M. Banks is forthcoming from University of Illinois Press. He has received the Thomas Clareson Award from the SFRA, and the Best Non-Fiction Award from the BSFA.

>> Read Paul’s introduction and shortlist.

3 Comments

-

I just finished Azanian Bridges this afternoon and agree wholeheartedly with what you say about it being a raw and splintery kind of novel. It isn’t great writing but it bites nonetheless. I was interested particularly in some of the underlying themes, especially the role of empathy and education in catalysing change. Many of the novels characters are motivated by a belief that building sympathies between white and black South Africans, allowing them to imagine the Other, is key to overcoming the apartheid state. The systemic power dynamics were marginalised by the story in favour of focusing our attention on the interpersonal day to day of the racist state. I can’t decide whether that is woefully naive or beautifully human. (Or, more probably, both.)

Pingbacks

-

[…] “Azanian Bridges by Nick Wood: a review by Paul Kincaid” […]

-

[…] commentators have already discussed the alternate history setting of Azanian Bridges (Paul Kincaid on this site and Gautam Bhatia at Strange Horizons, while Mark Bould also provides a useful list of other […]