By Vajra Chandrasekera

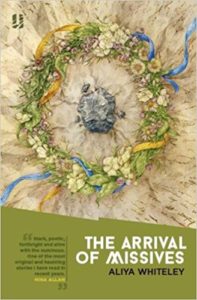

The Arrival of Missives — Aliya Whiteley (Unsung Stories)

Time travel TV shows can be broadly divided into two categories based on whether they’re about conserving history or changing it. On the one hand, Legends of Tomorrow or Timeless are about characters from our present preserving the status quo of our past, no matter how many historical atrocities must be committed to make that happen. On the other hand, 12 Monkeys or Travelers are (generally better) shows about characters from our future attempting to change the status quo of their past: our present is the error they’re setting out to change. The first category is big on costumes and cliché historical settings. The second is usually about future dystopias that must be prevented by taking action in our present: depending on budget, we may see more or less of the future dystopia itself, which features its own set of clichés.

Time travel TV shows can be broadly divided into two categories based on whether they’re about conserving history or changing it. On the one hand, Legends of Tomorrow or Timeless are about characters from our present preserving the status quo of our past, no matter how many historical atrocities must be committed to make that happen. On the other hand, 12 Monkeys or Travelers are (generally better) shows about characters from our future attempting to change the status quo of their past: our present is the error they’re setting out to change. The first category is big on costumes and cliché historical settings. The second is usually about future dystopias that must be prevented by taking action in our present: depending on budget, we may see more or less of the future dystopia itself, which features its own set of clichés.

Travelers in particular is one of the better science fiction shows on TV lately. It’s a low-budget show, light on the fx and heavy on the high concept. We don’t see the future dystopia directly; we only see it in the estrangement of the travelers, the presences they note with joy and wonder, allowing us to register them as corresponding future absences: the clean air, the trees, the birdsong. What differentiates the travelers in Travelers from the ones in 12 Monkeys (or Continuum, or The Sarah Connor Chronicles …) is that they are not a small band of plucky renegades, but part of an organized, civilization-scale collective project. Everybody left alive in the unseen Travelers future dystopia is working on this: many teams are sent back to our present, operating in cells and working on many problems at once. It is understood that the problems of the future do not derive from some particular single event that the time travelers could easily prevent. There is no particular villain to shoot, no bomb to defuse. And because of this, the project is dynamic, as the future adjusts to consequences and sends further instructions. The goalposts are always moving. And all the missions on Travelers are one-way trips: all these people are exiles from the future, committing the rest of their natural lives to the project. That is, they are exiles not only from the future that they came from, but also from the better future that they are creating. This is a leftist/sfnal well that many writers have drawn from before. There is a desperate romance in the double alienation both from the inaccessible future and from the uncomprehending present.

I am that exile

from a future time

from shores of freedom

I may never know …

— Sol Funaroff, “The Bellbuoy” (1938)

Nearing the end of Aliya Whiteley’s The Arrival of Missives, we think we’ve learned that it’s the second kind of time travel story: a story about a future attempting to change the past to change itself. Though here there are no travelers at all. All that is sent back are messages, the titular missives. Only information. The future is spamming the past with propaganda, hoping that of all the people who receive it, at least a few will be receptive, will be radicalized, driven to action.

Imagine reaching the point where there are no further allies to find, and so, in desperation, you write a message and place it within a bottle and throw it into the ocean. You hope and pray it will reach somebody who will feel the same as you, and who will find a way to aid you across that great expanse of ocean. That maybe they will save you. You pour all your persuasion into that message, and you cast it adrift; you have no inkling as to what kind of person might find it. You can only hope that it is picked up by somebody who shares your beliefs. Perhaps, if you send many such messages, some will wash up on fertile soil.

It matters that these communications are missives. They are entirely static and unidirectional. There is no access to consequences, no adaptation, no movement. The future is not listening, only speaking.

As Jonathan’s review covers in detail, Missives is written from the point of view of a young English woman, Shirley Fearn, who has a crush on the new local schoolmaster, Mr. Tiller. The story is set in early 1920, during which Shirley gradually learns that Tiller is an agent of a distant future that is attempting to change her present in a very personal way. Shirley is not the object of Tiller’s machinations, but his instrument: he wants to ensure that a particular young couple in her village don’t marry, so as to render their line of descent nonexistent. Sort of like Terminator, if the Terminator didn’t attack John or Sarah Connor, but instead sabotaged Sarah’s grandfather’s marriage before they had children. Tiller attempts to use Shirley to break up that marriage before it happens, escalating to violence as his original plan fails.

Tiller was recruited during the war; as a soldier and near death, he encounters the missive as a rock-like object that embeds itself in his body, in what would have otherwise have been a fatal wound. It preserves his life and lets him experience the future’s propaganda as visions when he touches it. When we meet him, he’s a true believer, completely committed to bringing about the future that the future demands of him. His error is in bringing Shirley into his confidence, in attempting to recruit her by allowing her to receive the missive as well. Afterwards, Shirley reflects on Tiller:

He is not mad. He is brave, and determined. He is utterly mistaken in his loyalty. He has taken the vision as undisputed knowledge rather than a point of view. He does not see that this future is not his fight.

Shirley is less susceptible to the propaganda of the future because she is not its target audience. Tiller accepts the missive’s assertions uncritically, that its eugenicist patriarchal white supremacist future needs defending, because it’s aimed directly at people like him. He sees only what the future is arguing for, not what it’s arguing against, because that dystopia is only an extension of systems that were already well in place by 1920. Tiller already understands capitalism, empire, and patriarchy to be good, solidly British, desirable things; how could he see their logical endpoints as anything but perfection? It doesn’t even occur to him that Shirley might find this future alienating instead of uplifting, or that it might drive her to desperate opposition. Which it does—the book ends on a declaration of war, where Shirley abandons her old plans for her own life to hunt down other agents of the future and destroy them. The empire, reaching back through time, is creating not only its fanatical adherents but an equally fervent resistance.

In 1835, Kylas Chunder Dutt wrote a short story called “A Journal of Forty-Eight Hours of the Year 1945”, published in the Calcutta Literary Gazette. It’s one of the earliest published English-language short stories from South Asia, and it’s a science fiction story about a rebellion against the British Empire 110 years in the future—the rebellion fails, incidentally, which is more pessimistic than one would expect from such a young writer (Dutt was eighteen at the time), but I suspect that Dutt was setting out to write about resilience in the face of defeat, not about the end of Empire. It is very clearly a polemic, deliberately seditious. It was, if you like, propaganda from a particular future, all the more remarkable for its prescience. And of course Dutt’s future 1945 is still a quarter-century in the future of The Arrival of Missives, whose little struggle between competing futures may seem to take place in an idyllic English village, but actually takes place in a horrific dystopia of its own. To take only a single example, Shirley and Tiller’s story is taking place more or less simultaneously with the Jallianwala Bagh massacre and its immediate aftermath.

Almost any future can be argued for in a way that (briefly, at least) might make it sound desirable; anybody can claim to be an exile from the future, a true believer. This is also very much a story about how history is written, and by whom, and for whom. History is written by those who have power, but this isn’t just the battleground of the history textbooks: history is constantly being written as it is made. One could even go so far as to define power as the ability to impose narrative on events; to repress and reinterpret history even as it happens, so that even the future’s primary sources will contain those distortions. As Churchill said of his WW2 memoirs, “this is not history—this is my case.” In Travelers, the future’s understanding of our present sometimes includes dangerous misunderstandings based on inaccuracies in the historical record. In Missives, the future attempts to retroactively impose those distortions on the past, to make its narrative of an endangered perfection as compelling and contagious as possible.

This is a tempting but dangerous romanticism, Missives argues, because it’s agnostic to principle. Which is why principles matter, of course. Missives constructs an argument against romanticism using the voice of a romantic young woman, which is why the process of her working her way through various romantic illusions is significant. And the novum—that the future is a dystopia attempting to preserve itself, not a utopia struggling to be born—works because we are already familiar with the grammar of time travel stories, so that we too are tempted to read Tiller sympathetically at the outset. After all, he has a mission and a big picture, which everybody else in this parochial village lacks. Shirley learns to read the missive critically, but too late to save a life. The necessity and method of reading against the grain is what feels to me like the heart of The Arrival of Missives. Shirley has to teach herself how to do this from scratch. The sheer preponderance of time travel narratives here in 2017 that rely on the same devices and uphold the same politics as Tiller’s future space nazis suggests that this has never stopped being necessary.

*

Vajra Chandrasekera is a writer from Colombo, Sri Lanka, and a fiction editor at Strange Horizons. His short fiction has appeared in Black Static, Clarkesworld, and Lightspeed, among others. He blogs occasionally at vajra.me and can be found on Twitter at @_vajra.

>> Read Vajra’s introduction and shortlist.

1 Comment

Pingbacks

-

[…] Shadow Clarke site was some of the most insightful writing that project offered up, in particular this review of Aliya Whitely’s The Arrival of […]